Empathy, Direct Experience, Violence and Will

Text for show "Modernismo Italiano" at Lia Rumma Gallery, Milan 2018

The Early Phase of Italian Modernism (1880-1920)

Part I: General Remarks on the Proposed Exhibition

Introduction

The following text is a preliminary proposal for an exhibition about Italian modernism that Clegg & Guttmann are planning for Lia Rumma Gallery in Milano. The ideas mentioned in the proposal are tentative and subject to change; the main reason for writing the proposal at this early stage is the need to begin a concrete discussion about the planned exhibition. The recent Clegg & Guttmann installation in the Kunstmuseum Basel on the topic 120 Years to the First Zionist Congress in Basel may be used as a rough guide for understanding the show we propose. The comparison with the Basel show is merely a heuristic, though; the projected exhibition at Lia Rumma Gallery will likely differ from the Basel exhibition in significant ways.

A schematic description of the planned exhibition

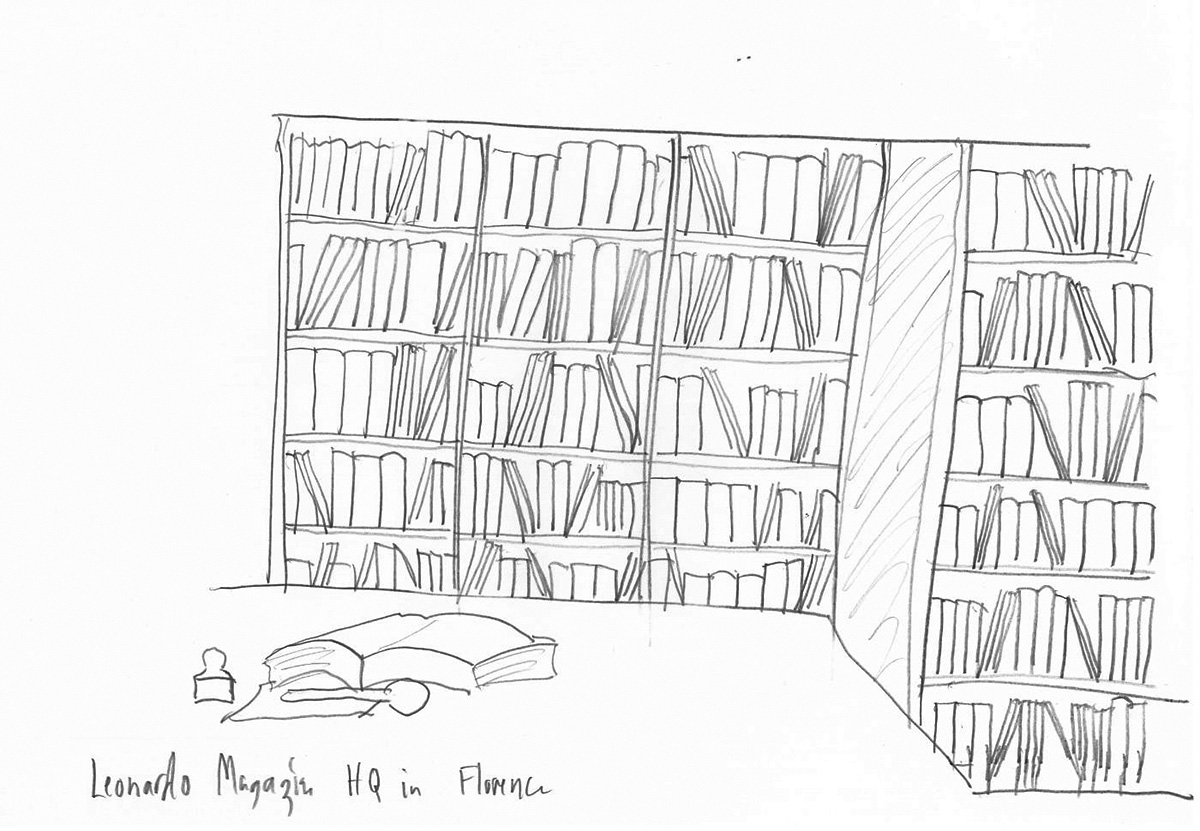

Early Italian Modernism (the title will probably change) is planned for the ground floor of the gallery (alternatively, for all the three floors.) The exhibition will consist of six to twelve small environments spread throughout the gallery; each of them will be a constellation of objects, photographic portraits and furniture ensembles that represent a context where one of the aspects of early Italian modernism was developed – an artist studio, a futurist sound studio, a socialist club etc. The environments are supposed to belong to specific individuals or groups who contributed to early Italian modernism; each is dated and localized – the office of Leonardo Magazine in Firenze 1903, for example - indicating that the relevant events took place in a certain time frame in a particular part of Italy. A schematic map of Italy should be drawn with chalk on the gallery floor so the different environments can be placed thereon according to their locations.

Each of the environments is based on a specific photograph or a painting; the objects in the environments will be partly period pieces and partly 'schematic' representations made of MDF. Some of the environments will include reading materials – newspapers, books etc.

Italian Modernism as an 'operatic' artwork

The main source of information about the protagonists and their activities are MP3 players attached to each environment that contain recordings of quotations of the protagonists, samples of their writings or music and texts about them. The audio-files will be playing simultaneously in order to create a 'sound environment' with a musical logic. When viewers approach nearby an MP3 player, they will be able to focus on the individual recordings it contains.

'Re-animated' portraits

The exhibition will also include portraits of the different protagonists. These portraits are based on black and white photographs that the artists 're-animate' – the photographs are enlarged and printed in color in order give them the character of Clegg & Guttmann portraits. The artists developed the technique in order to allow the viewers to immerse themselves in the portraits of a highly impressive group of young Italians that brought the early modernist culture to Italy.

Italian Modernism as 'art-essay'

The projected exhibition belongs to a group of Clegg & Guttmann installations the artists refer to as 'art essays'; the artists have been constantly developing new strategies for presenting relatively complex bodies of ideas in that form. The reason behind the persistent interest of the artists in this category, that included some of their most ambitious works to date, is twofold:

(i) The immersive qualities of the visual work of art help sustain the viewer's attention during complex, non-conventional presentations of intricate historical and philosophical material. The texts, audio files and objects are designed to appeal to the different mental faculties – a combination of sensual, intellectual and emotive stimulations that deepens the engagement with the topic.

(ii) The intense intellectual engagement the art essay typically requires tends to transform the aesthetic experience; the background information on the objects in view and the role they play in the historical processes bestow on them a distinct type of aura that deepens the viewer's engagement and gives rise to an aesthetic experience of a new kind.

Clegg & Guttmann are, needless to say, far from being the only artists interested in art-essays. In fact, some of the legendary shows at Lia Rumma gallery featured important practitioners of the art essay genre who developed in those occasions ground-breaking strategies for essaying with art – Kosuth, de Dominicis, Kabakov and Mucha, for example.

Part II: On Early Modernism

The need for a better understanding of early modernism

The starting point of the present proposal is that there is an urgent need for a better understanding of early modernism. Despite the attention given to topic, we believe that the contemporary discourse about modernism suffers from systematic misunderstandings that stem from uncritical acceptance of various dogmas; as a result, the meaning of the crucially important concept is consistently misconstrued.

(i) The most pervasive misunderstanding is that modernism was a rationalist, scientific world-view. In fact, the modernist movement began as a revolt against reason; all of the important and influential early modernist philosophers - Schopenhauer, Mach, Bergson, William James, Nietzsche and Charles Pierce - were highly critical of the exaggerated role assigned to the intellect and argued for the centrality of the will, direct intuition and the capacity for empathy. That does not mean that modernism was anti-scientific - it was a critique of science in the name of science.

(ii) The idea that modernism expressed an uncritical infatuation with technology, metropolitan life, industrialization and science is widely assumed to be a truism. In fact, most of the early modernists had an ambiguous relation to the modern lifestyle and sought to reform it.

(iii) Another common mistake is that the modernists had a disdainful attitude towards the past and a delirious belief in the future. As a matter of historical fact, many of the early modernists were involved in an array of revivalist movements that studied 'primitive' culture, the Middle Ages or even the Baroque as a way of transcending the cognitive limitations of their day and age.

(iv) The contemporary tendency to associate modernism with abstraction misses an important point: To the extent that they wanted to rid their art of representational content, the early modernists were motivated by the desire to come closer to the immediate, concrete reality of colors, lines, shapes and materials.

The dogmatic belief in rationality and scientific reasoning was typical of the second, post-war phase of modernism; after WWI, many associated the violent nationalist mentality that led to the war with the irrational exuberance of the early modernists who enthusiastically supported it. The wide spread tendency to blame the revolt against reason for the horrors of the Great War swung the pendulum in the opposite direction - it created an aversion towards anything mystical, spiritual or irrational; the result –a dogmatic, categorical belief in scientific rationality - was at the core of the new version of modernism that developed in the inter war years.

The politics of the early modernist Avant-garde

The pervasive view that the modernist Avant-garde was an integral part of the culture of the Left is yet another example of the stubborn unsupported dogmas that blind us to the true intellectual history of early twentieth century. In fact, the division between Left and Right as we know it today did not yet exist until the Russian revolution and the end of WWI; early modernism developed relative to an earlier world view and thus cannot be easily classified as belonging to either camp. If anything, many of the early modernists were decadent aesthetes who were staunchly a-political; after WWI some of them became right-wingers – Marinetti and Kirchner for example – while others supported the Bolshevik Left.

In Italy, the dogmatic argument that fascists cannot be modernists was particularly harmful; it obscured the central contributions of right wing Italian philosophers, writers, political theorists and visual artists to early modernism. Marinetti, for example, was, indeed, a fascist whose political and aesthetic ideas were tightly interconnected; does that fact call into question the veracity or authenticity of his modernism? Is there any doubt that his futurist manifesto provided one of the most influential and internationally celebrated formulations of early modernist ideology? In fact, the Italian Avant-garde poet participated in the events that led to the emergence of early modernism in Paris; he took part in the discussions of the cubist group that met in Pateau; he corresponded with Tristan Tzara and other Parisian Dadaists; due to his influence, futurist groups were founded around the world that brought early modernist culture to places like Czechoslovakia Georgia, and Nigeria. The reservation about Marinetti's modernist credentials is not supported by historical facts.

Part III: Direct Experience, Empathy, Violence and Will: Four Early Modernist Themes

Direct Experience

One of the complaints of the early modernists was that bourgeois culture functioned as a filter that led to a dull, distorted perception of the world. The revolt against reason sought to reverse or counteract this process by teaching people how to neutralize their reason and bring forth other cognitive relations to reality that will make it more resonant and engaging. The point was not to project one's subjective point of view on reality; quite to the contrary, the idea was that when one sets the concepts aside and engages directly in 'sense data' – with what one actually sees and hears – one might obtain access to a layer of important information that is usually suppressed and hidden from view.

Bergson argued that one of the victims of out over-intellectualized worldview was the perception of time. The French philosopher contrasted the 'mechanical' notion of time made of points that we are taught in school with 'duration' or the direct experience of time that was indivisible and forward looking. In the same years William James introduced the stream of consciousness as the basic object of psychology and proposed to investigate it 'in its own terms'. The two philosophers exerted important influence on Proust, Joyce, Woolf and other early modernist writers.

Empathy

In the social domain, the urban bourgeoisie were willing and able to 'filter out' the extraordinary poverty and misery surrounding them. In that period cities like Torino and Milano quintupled their population in less than fifty years, a process that resulted in a large segment of the population living in horrifying conditions. And yet there seemed to be a distinct lack of empathy for the victims of modernity. The rebels against reason blamed the same over-intellectualized world-view of the bourgeoisie for keeping urban misery from their view.

The idea created a shared ground between socialists who tried to 'open people's eyes' to the problems of the proletariat and decadent bohemians who wanted a more exciting world: Both were anti-bourgeois who tried to force people to take off their sunglasses and see their environment as it actually was.

Apart from its obvious social implications, the notion of empathy was useful also in the cognitive domain: In that context it signified the type of intense engagement generated by the neutralization of reason. Rodin's contemporary experiments with continuous drawings – when the eyes do not leave the subject and the hand draws automatically, as it were – were seen as proofs of the theory: when you keep concepts from view and focus only on the direct experience the results are often surprisingly life-like. In that context, too, neutralizing reason may lead to heightened empathy and the later, to an access to a new layer of facts.

The will as a central concept of modern philosophy

Schopenhauer defined the core of modern philosophy as the insight that "all our ideas are nothing but brain functions." According to his definition the philosophy of modern times calls into question any attempt to identify our internal representations with real, independently existing objects. The first philosopher to focus on these modern doubts was Descartes; in fact, the ability to doubt was central to his proof of the existence of the 'I'. Kant doubted the reality of the objects we perceive even further; he stipulated that we cannot have access to objects as they exist in and of themselves. Schopenhauer agreed with Kant but introduced the thesis that even though we have no way of knowing what lies beyond appearances we may identify a will behind them; even a wave that swells to its maximal size and then recedes displays such a will. Mach applied the modernist doubt to physics; he argued that even basic concepts like matter and energy have no independent reality. Science, in Mach's view, merely expresses the 'will to explain'; the concepts we use make the world intelligible to us. The will had a central role in Nietzsche's philosophy as well - he spoke about the will to power as the basis of his godless ethics; Bergson who was fascinated by the fact that sunflowers always turn their heads towards the sun concluded that they displayed a universal will to live; William James placed the will to believe despite insufficient evidence as the cornerstone of his pragmatist philosophy. The early modernists were overwhelmingly followers of Nietzsche, Bergson and William James; they believed that human beings were able to act autonomously despite their lack of access to the world beyond appearances due to their will.

Georges Sorel's political conception drew on the philosophy of Bergson and James; in this context too, the political theorist reasoned, the crucial notion is the will to believe. In so far as ideologies entice us to act, they should not be formulated as scientific theories as Marx required but in terms of evocative 'revolutionary myths' that make us throw caution to the wind. That was the basis of Sorel's syndicalism that profoundly influenced the revolutionary Left and the extreme Right. Indeed, both Lenin and Mussolini were deeply indebted to Sorel's idea of voluntarist politics. The rejection of science-based ideology and the assignment of a central role to the 'political will' made Sorel the godfather of modernist revolutionary politics.

The legitimation of violence

The most direct opposition to a life of reason was, of course, one ruled by brut force. Even if the early modernists did not initially intend to, their revolt against reason invariably turned into a joy of humiliating it and finally to a conception of life where violence played a constant part. For millions of young people in Italy, France, Britain, Germany, Austria and Russia, WWI turned that 'contrarian' attachment to violence into completely real challenge that they mostly enthusiastically accepted. The Futurists declared: "We will glorify war —the world's only hygiene —militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for women." Many of them died in the war.

The war brutalized Italy. As Gramsci put it: "Four years of war have rapidly changed the economic and intellectual climate. Vast workforces have come into being, and a deeply rooted violence in the relations between wage earners and entrepreneurs has now appeared in such an overt form that it is obvious to even the dullest onlooker. No less spectacular is the open manner in which the bourgeois state…shows itself to be the instrument of this violence."

The end of the war brought, in quick succession, a semi-revolutionary situation when hundred of factories were occupied and operated by syndicalist and socialist workers councils and a wave of vicious fascist counter-violence that culminated in the March of Rome of 1922.

Part IV: Italian Modernists

Early modernism in Italy

Italian modernism developed in the background of the intense industrialization, urbanization and political unrest of the period between the Risorgimento and the First World War. After the bourgeoisie completed their domination of every aspect of economic, social and political life, modernism emerged as an anti-bourgeois movement with philosophical, cultural and political wings. In the philosophical realm modernism was associated with the revolt against reason, which was associated with bourgeois ideology, and the celebration of intuition, empathy and the will. The period was also the first golden age of psychology that was researched both as a science of mental life – rational and irrational - and the means to control it. These ideas influenced the symbolist movement that aimed to produce on the viewer certain mental effects rather than represent nature. The same influences were evident in the political domain. The syndicalist politics of the same years sought to propagate revolutionary myths rather than rationally influence the masses. The rejection of 'bourgeois' dogmas – determinism, materialism etc. – had important consequences also in physics – field theory, quantum mechanics etc. - and mathematics – the 'subjective' foundations of probability theory, for example. In literature, early modernists tended towards the stream of consciousness techniques that were inspired by the writings of William James and Bergson.

Many of the conceptions of the early Italian modernists were influenced by the French discourse; the Italian versions were often highly original and distinctive, though, reflecting the conditions of the country. The next sections consist of short introductions to a partial list of the environments of the Italian early modernists that we plan to include in the exhibition.

The Florentine offices of Leonardo magazine

Giovani Papini led a group of young Florentine intellectuals that was known as the Italian pragmatists. Starting in 1903 the group began to publish a series of sophisticated magazines dedicated to philosophical and cultural issues. The first magazine was named Leonardo; it was followed by Lacerba and La Voce.

The Florentine pragmatists were influenced by British empiricism, positivism and pragmatism; when William James visited Italy and heard about his Italian disciples he initiated a meeting with Papini, Calderoni and the rest of the group; James' impression was highly positive – he said he wished his students at Harvard were as knowledgeable and sharp. Papini's crew met the futurists that gathered around Marinetti and after an initial tension, the two groups got along famously. In 1914, though, there was a split between the Florentine and Milanese. Both Papini and Marinetti became increasingly enamored with the fascist movement; the rightward turn of the former was reflected in the editorial policy of his magazines.

The Torino school of mathematical logic

One of the founders of Leonardo was a talented young mathematician named Vailati who was studying mathematical logic in Torino. Among the eminent teachers who taught him during his studies in the Torino mathematics department were Peano and Volterra. The Torino school of logic was known worldwide for its insistence on rigorous axiomatization and formal proofs. The reasoning behind the axiomatic approach to mathematics was philosophical: The logicians of the Torino school insisted that mathematical theories should be defined in terms of precise axiom systems that filtered out the metaphysical assumptions that often crept in. Mathematicians do not have to assume that their theories were true; the truth of the axioms systems that formulate them should be left open; the mathematician's aim is to prove that if the axioms were true certain consequences followed.

Vailati wrote: "It must be demanded of anybody who advances a thesis that he be capable of indicating the facts which according to him should obtain (or have obtained) if his thesis were true, and also their difference from other facts which according to him would obtain (or have obtained) if it were not true."

An international congress on probability theory in Rome

Bruno de Finetti studied mathematics and later became a professor in the University of Rome. His controversial, highly influential theory of probability is currently considered one of the most important treatments of the subject. De Finetti general philosophical point of view was influenced by the Italian Pragmatists and the Torino school: He followed the latter in his rejection of the idea that mathematical theories were objectively true. Instead, de Finetti recast probability theory in subjective terms, defining the probability of a proposition as the degree of belief an individual assigns to that proposition. Subjective probabilities reflect the betting behavior of the individual who assigns them - the way he or she would bet on various propositions. The sole requirement placed on the choice of subjective probabilities is internal consistency.

De Finetti's rejection of objective probabilities was motivated by a general anti-metaphysical spirit that stemmed, according to his explanation, from his hatred of 'bourgeois' metaphysics. Indeed, de Finetti saw a strong connection between his subjectivism and the anti-intellectualism of the fascists he admired. His 1931 paper "Probabilismo" for example closes with a remarkable pean to fascism that connected it to his philosophy of probability.

"But where my spirit rebelled most ferociously and clashed against the concept of 'absolute truth' was in the political field, and I could not say what part, surely very great, this sense of impatient revolt must have had in the development of my ideas. To be confronted by papier-mâché idols and a miserable political class that would have preferred Italy in ruins rather than failing (sacrilege!) to render due homage! Those delicious absolute truths that stuffed the demo-liberal brains! That impeccable rational mechanics of the perfect civilian regime of the peoples, conforming to the rights of man and various other immortal principles! October of '22! It seemed to me I could see them, these Immortal Principles, as filthy corpses in the dust. And with what conscious and ferocious voluptuousness I felt myself trampling them, marching to hymns of triumph, obscure but faithful Blackshirt."

The Grubicy gallery in Milano

The first Italian painting style that merited the designation modernist art was an odd combination of post-impressionism, symbolism and realism from the 1880's and 1890's that is often referred to as divisionism. Gauguin explained the symbolist painting style as a product of the desire of the artist to impact the viewer in a particular way rather than paint the world faithfully. With this aim in mind, Gauguin painted the earth in Sermon in the Afternoon bright red, for example; it did not matter to him whether or not the color corresponded to nature. Symbolism can be explained as a reflection of the modernist belief that the viewer has no access to the object in and of itself but only to its appearances. According to the modernist the idea of a faithful depictions stems from confusion; since the viewer never accesses the object itself what does the faithful depiction thereof mean? The only aspect of the painting process that has any relevance is the way the painted surface impacts the mind of the viewer.

In Italy the Scapigliatura movement developed an interesting confluence of symbolist and divisionist (re: post impressionist) ideas. The movement consisted of a group of bohemian artists and writers who were active in Milano from the 1880's. Grubicy, an art dealer and critic who opened a gallery in Milano, exhibited and supported some of the artists in the group. The art dealer spent a period of time in Paris where he became acquainted with the ideas of the symbolist movement and upon his return to Italy introduced them to Segantini and other talented local painters.

Segantini, like Van Gough, combined the symbolist use of color with intricate post-impressionist brushwork. Even though Segantini's paintings were not wild as Van Gough's, he shared the latter fascination with 'kinetic' surfaces that seemingly swirled and other 'psychoactive' effects that existed only in the mind of the beholder, emphasizing the symbolist ideology. The methods of the Scapigliatura to introduce motion into paintings influenced the futurists - Severini and Boccioni in particular.

Volpedo, another member of the Scapigliatura and one of Segantini closest friends introduced into his art the type of political subject matter used by 'realist' painters. The combination of realist subject matter, symbolist use of 'unnatural' colors and 'psychoactive' post-impressionist brushwork made paintings like The Forth Estate truly haunting.

An 'Austrian' café in Trieste

The writer Italo Svevo was born in Trieste to a Jewish father and an Italian mother. He completed Confessions of Zeno, his masterpiece, when he was over sixty. The novel tells the story of Zeno, its narrator, who was instructed by his psychoanalyst to write his memoires as an aid to his therapy. Consequently, we learn about him only how he appeared to himself and his analyst rather than how he actually was; he emerges from the words that describe him like a portrait in a pointillist painting – an 'I' that construct itself in the manner described by Mach in his Analysis of Sensations.

The book revolves around the narrator's tobacco addiction and his constant attempts to stop smoking: Whenever he manages to do so for a while he initially experiences such elation that he starts smoking again so he will be able to stop again and experience once more the state of mind he longs for.

Zeno was a close friend and early supporter of James Joyce when he lived in Trieste. Joyce, in turn, was instrumental in bringing Svevo's writings to the attention of publishers, editors and critics.

A room of an 'individual' anarchist

Novatore was an individual anarchist who embodied the irrational hyper-individualism of early modernism in its most violent, political form. A son of peasants from Liguria, he self-educated while toiling the fields, reading Nietzsche, Stirner and Baudelaire. If god was dead - as the first said - the only one you owed anything to was yourself – as the second did – and that meant living life to the fullest – like the third. Politically, Novatore was influenced by the revolutionary anarchism of Malatesta and Kropotkin.

"Revolution, he wrote, is the fire of our will and a need of our solitary minds; it is an obligation of the libertarian aristocracy. To create new ethical values. To create new aesthetic values. To communalize material wealth. To individualize spiritual wealth. Because we - violent cerebralists and at the same time passionate sentimentalists - understand and know that revolution is a necessity of the silent sorrow that suffers at the bottom and a need of the free spirits who suffer in the heights."

Novatore believed he had the right to expropriate from the rich what he needed for daily survival and justified the use of force.

From 1908 on Novatore embraced individualist anarchism. In 1910, he was charged with burning a local church and spent three months in prison but his guilt was never proven. A year later, the police accused him for theft and robbery. Renzo Novatore was involved in an anarchist-futurist-collective in La Spezia that he led (with Auro d'Arcola) and molded into an active militant anti-fascist Arditi del Popolo. In May 1919, the city of La Spezia fell under the control of a Revolutionary Committee and Novatore fought alongside the revolutionaries.

When Italy was about to be taken over by the fascists, Novatore went underground. In 1922, he joined the gang of the famous robber and anarchist Sante Pollastro. He was killed in an ambush near Genoa on November 29, 1922.

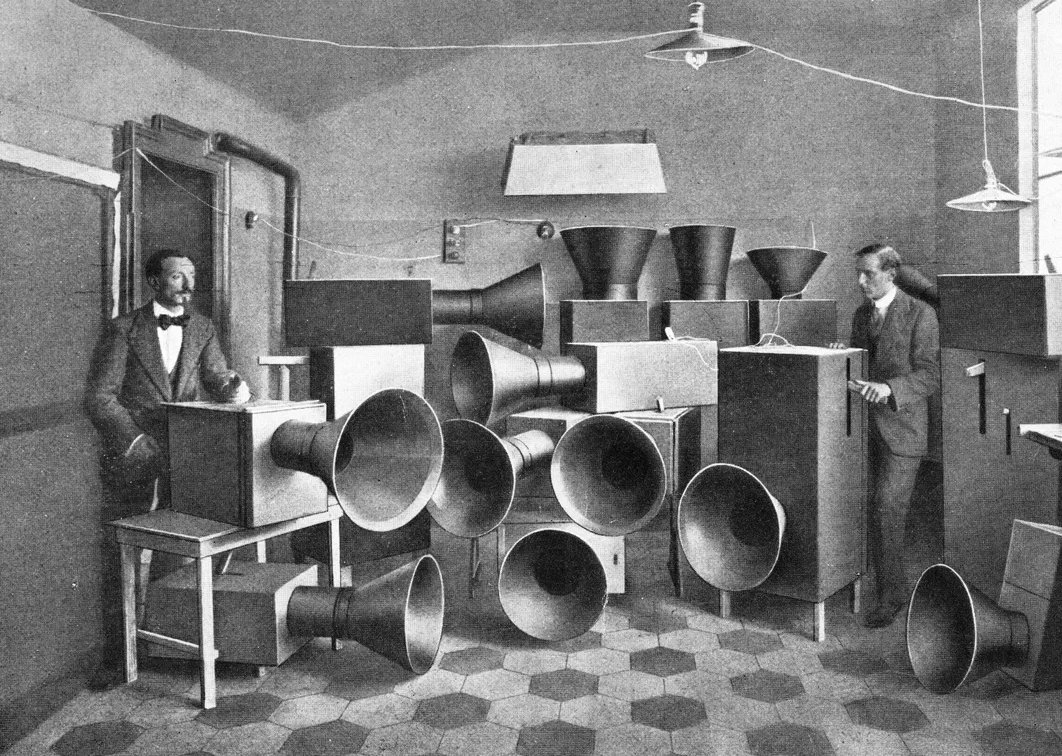

A Futurist sound studio

Russolo was an Italian futurist painter, composer a builder of experimental musical instruments and the author of the manifesto The Art of Noise. He is often regarded as one of the first experimental composers. Russolo performed noise-music concerts in 1913–14 and continued them after World War I - notably in Paris in 1921. He designed and constructed noise-generating devices he named Intonarumori.

Explaining his musical approach, Russolo wrote:

"At first the art of music sought purity, limpidity and sweetness of sound. Then different sounds were amalgamated, care being taken, however, to caress the ear with gentle harmonies. Today music, as it becomes continually more complicated, strives to amalgamate the most dissonant, strange and harsh sounds. In this way we come ever closer to noise-sound."

Russolo and Marinetti gave the first concert of Futurist music, complete with intonarumori, in 1914, causing a riot. The program comprised four "networks of noises" with the following titles:

- Awakening of a City

- Meeting of cars and airplanes

- Dining on the terrace of the Casino

- Skirmish in the oasis